I grew up on the coast in San Diego. I knew the ocean. I knew the beach. I swam in the waters, body surfed, and boogie boarded. I caught crabs on the shore and dragged kelp to my sandcastles. I tasted salt water on my lips, felt the stickiness on my skin, and experienced days of getting sand out of my hair clinging to my scalp, stuck in place by the tumbling waves.

In 5th grade our teacher, a former marine biologist, took us to the tide pools. Minute by minute, hour by hour, he showed me things I’d never seen in the ocean. He taught us what we could touch and what we couldn’t. We found an octopus and he taught me how to gently lift it from its hiding place, observe it with care and respect, and release it back into its home. I felt sharp barnacles and learned why they adhere to rocks and that they also hitch rides on whales.

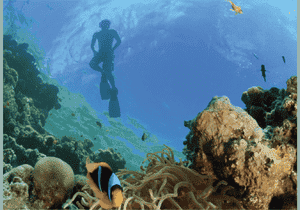

Fast forward several years; my mom takes us to Hawaii where for the first time I put on a mask and snorkel. We were on the island of Maui behind the Hyatt Regency, and I stuck my head under the ocean surface and nearly cried. I had never seen anything so beautiful, so colorful. The little teenage me shook with excitement as I told my mom, “It’s just like on TV! It’s like a movie! I can’t believe I’ve never seen this before!”

Fast forward 10 years; I’m now married, and we have an opportunity to go back to Hawaii and I get to scuba dive for the first time. At these depths I see sharks, electric eel, a whole different layer of the ecosystem. And once again I’m wrapped in awe at all there is to know.

If we think of language as an ocean, we might see reading and writing as the skills needed to swim. With these skills students can go deeper. They are free to explore, create, and express. And they can find joy and reward in doing so.

Sadly, so many kids in our nation do not get the early exposure, explicit instruction, and regular practice they need to become excellent language “swimmers.” That is to say they miss the basic skill-building experiences needed to master reading and writing and because of that many children are drowning. They do not find joy or reward in doing the work it takes to improve because their lack of skill prevents them from accessing the intrinsic thrill of accomplishment.

We educators and parents do well to remember that reading and writing are not innate. They are of human construct and as such must be imparted with intention and care. We are giving children life-long skills that will directly affect their life experience. It will affect their way of thinking, their way of communicating with others, their career decisions, and hobbies. How we read and write will affect how they interact with others—their families, friends, and society.

Language is an ocean. Our children will stay in the shallows, limited to what is seen right in front of them, if we do not give them the time, tools, insights, and practice that can help